What to Know About Anxiety and Depression With Parkinson's Disease Psychosis - HealthCentral.com

Mental-health struggles go hand-in-hand with this challenging condition. Here's your roadmap to relief.

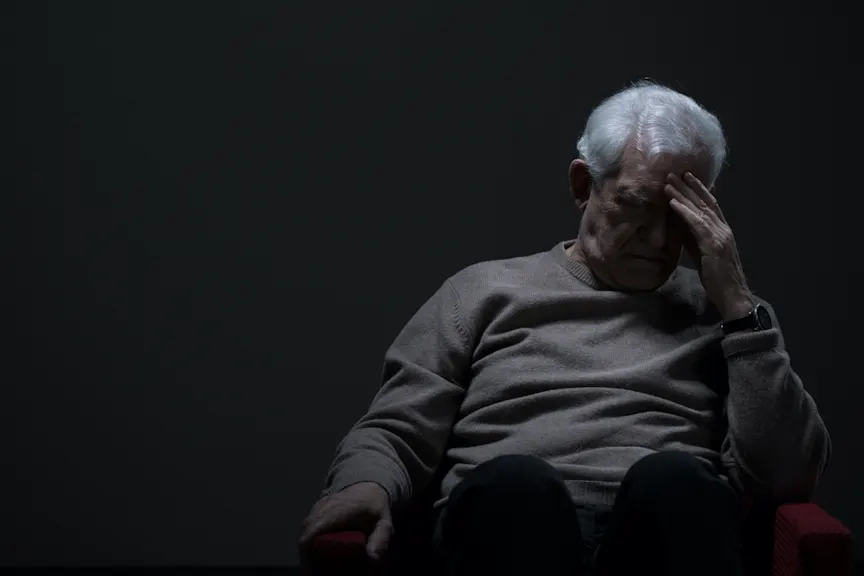

iStock

It's a vicious cycle: Parkinson's Disease (PD) leads to depression and anxiety, which research suggests can contribute to more and worsened symptoms of Parkinson's disease psychosis, including hallucinations, delusions, and memory loss. In turn, having PD psychosis can leave you feeling anxious and depressed. But you don't have to just "live with it." There are things you or your loved one with PD can do to ease mental-health struggles and stop, or at least slow down, the cycle. Here's what we know about the relationship between mental health and PD psychosis and how your healthcare team can help.

The Parkinson's Psychosis and Depression Link

Anywhere from 20% to 70% of people with Parkinson's disease will develop psychosis over the course of the disease. It can be caused by natural disease progression or as a result of the dopamine therapy used to treat PD. "The longer you have Parkinson's, the more likely you are to develop psychosis," says Rodolfo Savica, M.D., Ph.D., a neurologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN. A hallucination is when you see, hear, feel, or taste something that isn't there, while a delusion is a false belief. Between episodes, though, people with PD psychosis can be lucid much of the time.

In those intervals of lucidity, people with Parkinson's psychosis may feel embarrassed by their hallucinations and/or delusions. Realization of their loosening grip on reality can worsen or spark depression, says Dr. Savica. Likewise, the hallucinations and delusions themselves may cause depression; after all, believing that someone is trying to poison you, for example, is scary and stressful. Beyond that, the latest research shows that PD degeneration begins in the brainstem, which contains serotonin and adrenergic neurons, both of which play a big part in regulating mood. Understanding these connections can help you have more empathy with a loved one with PD psychosis.

How Anxiety Impacts Psychosis, and Vice Versa

One study from Emory University found that the severity of one's anxiety was a significant predictor of the number and severity of hallucinations and delusions they have. Whether the anxiety sparks the psychosis or vice versa is a chicken-or-egg question that researchers haven't yet answered, but it does mean that treating the anxiety separately may help the psychosis. The association could also be a useful warning: If your loved one with PD is an anxious person, they may be more at risk for psychosis. Talk to your doctor about treating the anxiety proactively.

For most people, anxiety manifests in an inability to relax, excessive worrying, and restlessness. PD patients have these symptoms, as well, but they may exhibit additional troubling warning signs. One 2020 study found that almost a quarter of people with Parkinson's will experience PD-specific symptoms including anxiety around driving, eating, and socializing. Why? Typical PD symptoms like drooling, slurred speech, and hand tremors are embarrassing and can make people with Parkinson's dread seeing friends or going out in public. Assure your loved one that no one judges them and encourage them to remain a part of a community—whether it's a church, a senior center, or a book club—for as long as possible.

Diagnosing Mental Health Issues With PDP

As interconnected as depression, anxiety, and psychosis are in people with Parkinson's, it's important not to lump them all together, says Joseph Quinn, M.D., director of the Parkinson's Center at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, a Parkinson's Foundation Center of Excellence. Your doctor will want to assess for and diagnose each condition on its own. "We ask about mood, sleep, appetite, and crying spells as markers of depression," says Dr. Quinn, "and we ask about hallucinations and delusions as markers of psychosis." Understanding the nature of the diagnoses will help your loved one get the best care possible.

"It's helpful to treat one thing at a time," says Dr. Savica, "so that we can be clearer about whether or not the treatment works." He says he tries to determine what the most bothersome symptom is for the patient and starts out treating that symptoms first. It might be that hallucinations and delusions are the most upsetting to you as a caregiver; after all, it's alarming to see your loved one interacting with someone who isn't there, for example. But if those episodes happen infrequently, it's very possible that constant depression is what's making your loved one's daily life feel bleak—and what should be addressed first.

Finding the Right Treatment

One hallmark of PD is the reduction of dopamine, the neurotransmitter involved in controlling movement, kidney function, sleep, motivation, learning, and pleasure. So a first-line treatment is dopamine agonists (DA), medications that mimic the neurotransmitter's actions and restore normal movement and mood. Over time, though, the same medicine that saved your loved one's life may cruelly turn on them. "After many years, these drugs can cause hallucinations, paranoia, compulsion, and memory loss," says Dr. Savica. If so, he starts fresh with a whole new, non-DA drug regimen. "There are a lot of ways we can tailor the treatment to the patient. Psychosis is not always an eventuality."

Depression and/or anxiety might be treated with antidepressants by the neurologist, but most doctors will also recommend talk therapy. Since symptoms of psychosis generally first appear between ages 55 and 65 and become more common in people ages 70+, it's worthwhile finding a psychologist or psychiatrist who specializes in geriatrics, says Dr. Savica. In one study, PD patients who received cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) by geriatric therapists experienced significantly less depression than those who didn't. One caveat: Therapy won't help with psychosis symptoms, says Dr. Quinn, but it can help ease the associated depression and anxiety.

The Importance of Movement

Exercise of all kinds can be vitally important for all PD patients, says Dr. Savica. Those who exercise a minimum of 2.5 hours a week significantly slow the decline in their quality of life compared to those who don't. Exercise has also been shown to play a big role in mood. People with PD who exercise more are less likely to experience anxiety or apathy than those who exercise less. Get moving with regular walking, water aerobics, Tai Chi, dance, Pilates, weight training—anything that's enjoyable enough to stick with it long term.

Bottom line: Yes, depression and anxiety are statistic likelihoods with Parkinson's psychosis, but your loved one is not a statistic, and you have options. Start with a call to their doctor to assess treatment options, then consider which therapies and lifestyle enhancements we've outlined—maybe search for a gentle water-aerobics class or a weekly low-key lunch with friends—might be doable. It may take trial and error, but there is a very real chance that better days are ahead.

Comments

Post a Comment