Psychiatric, cognitive functioning and socio-cultural views of menstrual psychosis in Oman: an idiographic approach - BMC Women's Health - BMC Blogs Network

Case report 1 (AA): premenstrual psychosis

AA is a 23-year old single Omani woman. She was brought by her parent to the psychiatric clinic with a 3-year history of the cyclical presentation of a short episode of clouded sensorium and abrupt onset of psychosis. Her thoughts and emotions had been impaired to the extent that her family had begun to believe that she had been 'possessed' by a malevolent spirit. Her mother noted that her distress occurred during the second half of her menstrual cycle and ended at the onset of menstrual bleeding. During the second half of her menstrual cycle, AA was reported as showing symptoms of dysphoric mania, isolating herself and crying unremittingly without substantive reason. The episodes of negativistic behavior tended to be superseded by a state of overactivity and euphoria characterized by grandiose beliefs, inappropriate irritability and social behavior and increased talking speed or volume. AA's symptoms were reported to recede upon the onset of menstrual bleeding. While sedulous dating was not feasible, she was described to have had approximately 6–8 episodes of 'possession' in a year, with a regular occurrence every month.

She had no relevant medical history and denied having a family background of persistent mental disorders. She also denied having consumed any mind-altering substances including tobacco or its rejuvenated forms and alcohol. A routine urine drug screening did not reveal the presence of any illicit drugs in her system.

Premorbid, AA met her developmental milestones without difficulty. AA had her first menstrual cycle at the age of 13 with regular cycles. She acquired 12 years of formal education and graduated with a secondary school leaving certificate with average performance. But due to her recurring distress, she did not seek further education or employment.

During her consultation in our unit (taking place after the onset of menstrual bleeding), the clinical team noted that she was asymptomatic, interactive and socially active. She informed the clinical team that she tended to have 'strange feelings' and 'weird experiences' starting during the second half of her menstrual cycle. Overall, she expressed foggy awareness of her recurring distress.

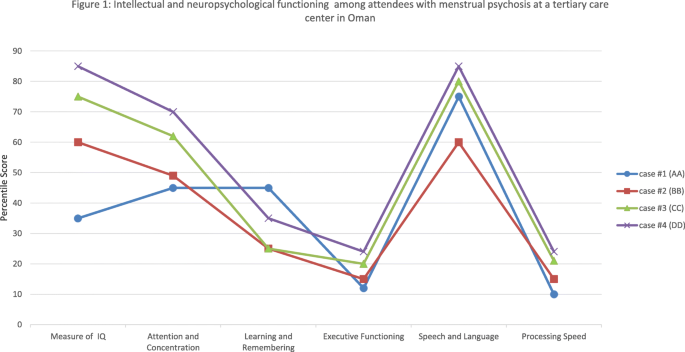

Physical examination was unremarkable and her medical workup—hormonal study, brain computerized tomography (CT) scan, and electroencephalogram (EEG)—was inconclusive. She was also subjected to neuropsychological testing and evaluation of mood (see Fig. 1). AA scored 23 on the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia [17]. Such a score implied the presence of moderate depressive symptoms.

Intellectual and neuropsychological functioning among attendees with menstrual psychosis at a tertiary care center in Oman.

Olanzapine (5 mg)—an antipsychotic—was instituted once every day to which she was deemed to be compliant. The clinical team noted that the severity of her distress significantly receded but still manifested in episodes of screaming and lability and, as often the case, dissipated upon the start of menstrual bleeding. As the symptoms appeared to be atypical to those featured in CIDI, the clinical team suggested the tentative diagnosis of a manic episode, unspecified (F309)/brief psychotic disorder (F24). During the subsequent follow-up, her antipsychotic, olanzapine, was tapered up to 10 mg once daily and it was noted that the patterns of her symptoms appeared to generally be aligned with her menstrual cycle.

During subsequent follow-up (6 months later), it appeared that her distress was exacerbated after approximately 28 days. Overall, her episodes of manic and psychotic-like symptoms remained the same but significantly reduced in terms of duration and veracity of distress.

Case report 2 (BB): Catamenial psychosis

BB is a 34-year-old married woman with 3 children from the urban part of Oman. She approached the unit at the present hospital with her husband and her female siblings who helped provide us with anamnestic data. According to them, BB went through clouded sensorium which lasted for a short duration. The distress was accompanied by abrupt onset of inappropriate emotions, trouble in concentrating, suspiciousness, and spending a lot more time alone than usual; episodes that tended to reappear monthly throughout her adult life. The family attributed her distress to ethnopathology. She had been taken to a traditional healer who recommended dietary changes, herbal medicine and attributed her behavior to an 'invading evil spirit'.

During these episodes, she had had poor self-care, hygiene, oral intake and a disturbed sleep pattern. She had once woken up at midnight to sprinkle her children with water. During exacerbation of her distress, she became suspicious of her husband and the female domestic servant. She displayed odd mannerisms and stereotypical behavior along with rituals of cleaning and washing. On one occasion, she had escaped from the house and was found wandering aimlessly in the neighborhood. At the time, it was also reported that she had been improperly dressed, in a manner that is deemed to be socially immodest in a rural, conservative society.

A protracted interview with her husband and siblings indicated that her distress tended to occur at the onset of menstrual flow. Her symptoms continued until the end of menstrual flow. She had a patchy memory of her state of clouded sensorium. She stated that she often felt tired and dysphoric during a certain time of the month which she attributed to stress at work.

Premorbid, there was no indication that BB had experienced any adverse life events during her childhood. She completed 12 years of education and later enrolled herself in a higher education institution to distinguish herself as a teacher. She has 11 siblings with no evidence of mental illness in the family. Her menses began at age 12.

BB denied having consumed any mind-altering substance including tobacco or its rejuvenated forms or alcohol. A routine urine drug screening did not reveal the presence of any illicit substances in her system.

Physical examination was unremarkable and her medical workup—including hormonal study, brain CT scan, and EEG—was inconclusive. The clinical team suggested that the respondent displayed manic episodes with psychotic symptoms or according to ICD-10, the client's distress might be parallel to a manic episode, unspecified (F309)/brief psychotic disorder (F24). CIDI did not indicate the presence of typical manic (F30), Bipolar affective disorder (F31), schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders (F20, F22, F23, or F25).

Her distress subsided immediately upon admission and she was discharged with antipsychotic olanzapine (5 mg) for which she was compliant. Following up a week later, she was deemed suitable for protracted psychometric evaluation. Her intellectual and neuropsychological functioning are depicted in Fig. 1. BB scored 21 on the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia [17] which implied the presence of moderate depressive symptoms. Six months later, still compliant to prescribed medication (olanzapine 5 mg), she reported two episodes of relapse but with less intense symptoms. The two episodes of relapse once again coincided with menstruation and subsided with the end of her menstrual flow.

Case report 3 (CC): premenstrual psychosis

CC, a 25-year-old, had been referred to this unit after she developed erratic behavior while traveling abroad. As detailed in the summary that was brought to our attention, she was sectioned under the mental health act and upon returning to her premorbid state, she was allowed to fly back to Oman. In the discharged summary, she was given a tentative diagnosis of an acute psychotic/manic episode. She responded when prescribed with Olanzapine (10 mg BD).

Upon arrival in Oman, she sought consultation with the present unit. The accompanying family member informed the clinical team of her distress while traveling abroad, of which CC has minimal recollection. The family informed us that she often experienced uneasiness with others and exhibited strongly inappropriate emotion and culturally devalued conduct in the last 5 years. They noted that the distress occurred periodically (approximately every 29 days) with abrupt onset during a full moon. In traditional Omani society, certain lunar cycles are thought to trigger bad omens and malevolent spirits. Her symptoms were deemed manageable by the family since they appeared to dissipate with lunar changes. Further exploration of her changed self and conduct appeared to occur during the second half of her menstrual cycle and end at the onset of menstrual bleeding.

Premorbid, her life during childhood was uneventful. She excelled in her education, graduated with a university degree and was on the lookout for a job. CC denied having consumed any mind-altering substances including tobacco or its rejuvenated forms and alcohol. A routine urine drug screening did not reveal the presence of any illicit drugs in her system. Physical examination was unremarkable and her medical workup—including hormonal study, brain CT scan, and EEG—was inconclusive.

CC and her family were offered the option of continuing with the same medication she was prescribed abroad. CC and her family refused the option under the pretext that the medicine (Olanzapine) left her feeling drowsy, constipated and with an insatiable appetite. The attending team labeled her of having something akin to a manic episode with psychotic symptoms. Using the ICD-10, she was registered in her medical records as having Manic episode, unspecified (F309)/brief psychotic disorder (F24) (Table 1). She was also subjected to intellectual and neuropsychological evaluation (see Fig. 1). CC scored 15 on the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia, a score suggesting the presence of mild depressive symptoms.

Case report 4(DD): premenstrual psychosis

DD is an 18-year-old female: single and living in an urban-suburban area of the national capital, Muscat. She was brought to the hospital due to a sudden onset of distress. According to the accompanying family, she had been having episodes of disruptive behavior, impaired vegetative functioning and problems fulfilling activities of daily living. When she came out of prolonged sleep, she made irrelevant conversations and had episodes of incongruent crying. These episodes were followed by increased hyperactivity and agitation. She displayed tangentiality marked by exaggerated euphoria.

Due to the perceived temporality of her distress, the family devised mechanisms within the household to protect her well-being until the erratic behavior had dissipated. The accompanying sibling informed the clinical team that DD appeared to suddenly become disturbed around the second week of the lunar month. The family recalled that her distress occurred almost every month in the last 2 years. On previous occasions, the family invited a traditional healer who 'diagnosed' her as being possessed by the jinn. The fact that she had had little insight into her altered state led the family to believe that her altered state of consciousness represented all the hallmarks of spirit possession. During psychiatric consultation, the clinical team noted that her distress receded and this coincided with the onset of menstrual flow. It appeared, therefore, that her symptoms had persisted until the onset of menstrual flow.

DD was said to have met all her developmental milestones without difficulty. In Oman, individuals require 12 years to complete secondary education. She recalled that her menses began at 12 years old. She was deemed to have been very bright during her secondary school but upon reaching puberty, due to the aforementioned symptoms, she was only able to finish 9 years of formal education. Thereafter, as often is the case in Oman, she stayed within the confines of her extended and polygamous family. She has 5 siblings and no evidence of mental illness in the family.

A routine urine drug screening was not significant, and neither were her hormonal study, brain CT scan, and EEG. Semi-structured interview, CIDI, did not confirm that she had the core features of manic (F30) and Bipolar affective disorder (F31), schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (F20, F22, F23, or F25). Rather, DD was deemed to be marked with something akin to manic episode with psychotic symptoms - Manic episode, unspecified (F309)/brief psychotic disorder (F24). The results of her psychometric evaluation are shown in Fig. 1, conducted when DD was stable.

Her disturbed behavior receded within 24 h of admission and she was discharged with antipsychotic olanzapine (5 mg) for which she was compliant. During the follow-up visit, she was stable and jovial and had already stopped her medication. The family and DD were given health education on how to adjust her life to accommodate for her predictable distress that occurred every month.

Comments

Post a Comment